Every fall, salmon leave the cold waters of Lake Ontario and begin a journey upstream, through the rivers, creeks and streams of the Greater Toronto Area, to reach their spawning grounds.

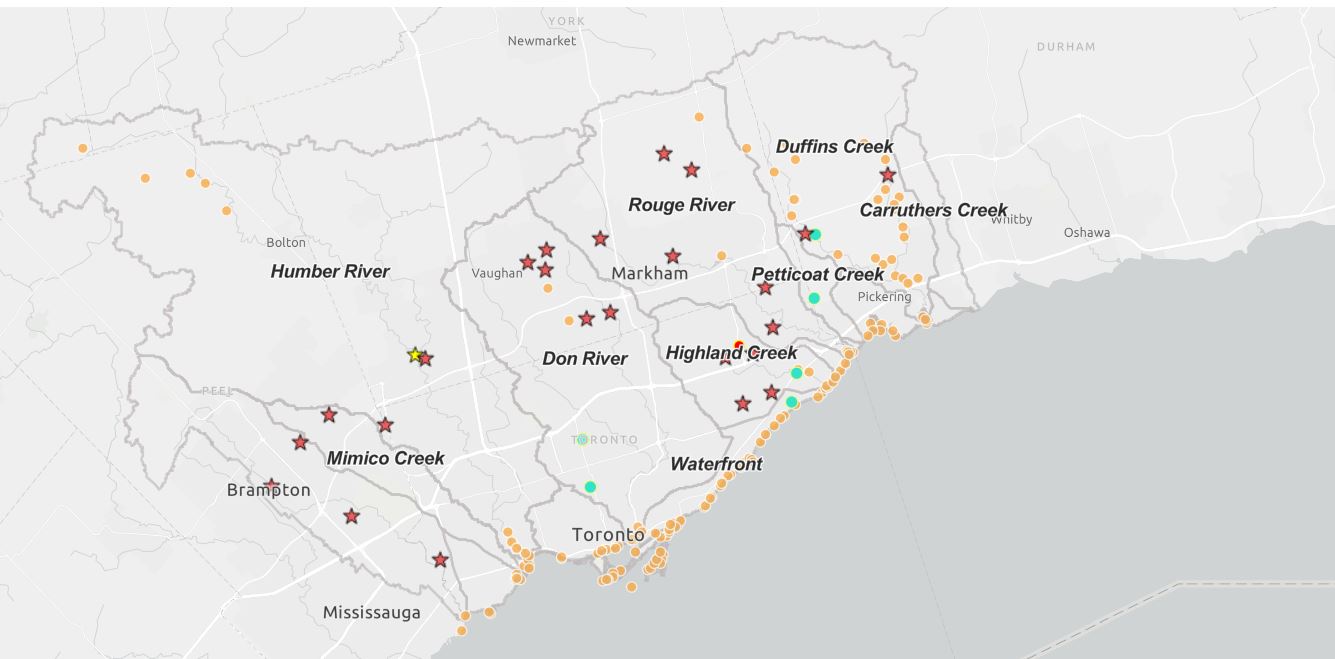

Explore the story of salmon in Toronto and region, learn about their extraordinary annual journey, and find out how you can help Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) monitor the state of our local salmon populations.

Spotting Salmon in Toronto and Region

Help TRCA’s monitoring team find migrating Salmon in regional streams and rivers! Submit your salmon observation today!

You can use our interactive story map to find the best places to spot Salmon and learn how to report any that you see.

Select the image below to open up the Salmon story map in a new tab.

Check the story map to find the best locations for spotting salmon during their annual migration.

Meet the Salmon

You will most likely spot one of these four members of the Salmonid family during their fall migration in regional streams and rivers.

ATLANTIC SALMON

Atlantic Salmon became locally extinct about 100 years ago due to human activities. This native Salmon is returning to Lake Ontario and its tributaries thanks to the Lake Ontario Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program. This photo depicts the distinct hooked lower jaw (kype) that develops in spawning male fish.

CHINOOK SALMON

Chinook Salmon are the most common Salmon observed in regional streams and rivers. The largest of the Pacific salmon species, they are often called King Salmon by anglers. Chinook and Coho Salmon were introduced and naturalized in Ontario to support local fisheries.

COHO SALMON

Coho Salmon are very similar to Chinook Salmon but smaller in size. These silvery fish are less commonly found in regional streams and rivers compared to Chinook Salmon.

BROWN TROUT

Brown Trout are the only Salmon or Trout with a square tail with spots in rows. Brown Trout and Rainbow Trout were introduced and naturalized in Ontario to support local fisheries.

The Story of Salmon in Toronto and Region

More than a century ago, Atlantic Salmon were commonly found in Lake Ontario and its rivers. With European settlement came an increase in negative impacts on aquatic habitat such as deforestation, pollution and construction barriers.

As a result, the population drastically decreased and by 1898 they were extirpated (locally extinct) from Lake Ontario.

Throughout the century, Chinook and Coho salmon were introduced to Lake Ontario to enhance recreational fishing and can now be seen in large numbers in the GTA’s rivers during fall migration.

In 2006, Lake Ontario water quality and habitat improvements allowed the initiation of an Atlantic Salmon restoration program.

HISTORIC TIMELINE

| 1812 | John McCuaig, Superintendent of Fisheries of Upper Canada, noted that Atlantic Salmon “swarmed the rivers so thickly that they were thrown out with a shovel and even with the hand.” |

| 1881 | Samuel Wilmot observes drastic environmental change, caused by European settlement, and laments that “the time is gone by forever for the growth of salmon and speckled trout in the frontier streams of Ontario” |

| 1898 | Atlantic Salmon extirpated from Lake Ontario as last confirmed fish caught off the Scarborough shoreline. |

| 1990 | Large numbers of Chinook and Coho discovered in the North shore tributaries of Lake Ontario, a result of intense stocking programs throughout the 1900s. |

| 2006 | Full-scale Atlantic Salmon restoration program begins in Lake Ontario streams. |

| 2011 | Atlantic Salmon restoration on the Humber River begins with the stocking of 100,000 fry. |

| 2017 | Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) records the largest Atlantic Salmon to be surveyed in the last 28 years (15 pounds) during their Lake Ontario fisheries survey. |

AN ORAL HISTORY

Listen to an oral history and storytelling of the history of the Atlantic Salmon in Southern Ontario by Curve Lake First Nation.

BRINGING BACK THE SALMON

The Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH), the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, and many other partners are working to bring Atlantic Salmon back to Lake Ontario.

The program has four major components: fish production and stocking; water quality and habitat enhancement; education and outreach; and research and monitoring.

To get involved with the program or for more information visit: bringbackthesalmon.ca

Learn More About Salmon

LIFE CYCLE

Select the image below to view full-sized.

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION

Select the image below to download a guide to identifying Salmon species of Lake Ontario.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Do fallen trees obstruct salmon migration?

A blockage would need to be quite substantial to keep a salmon from navigating upstream and to block migration, especially if there is still water flowing. Salmon have evolved to navigate natural objects in rivers and streams and are very powerful jumpers, known to jump as high as two to three metres.

The Salmonid species are quite determined to make their way upstream to spawn. Other than a dam, few obstacles will get in their way. Also, fallen trees create important habitat for aquatic insects and small fish.

Woody material is a natural function of a healthy river system and shouldn’t be removed unless absolutely necessary (e.g. such a significant blockage that its causing flooding, erosion, or risk to health and safety).

What effects do weirs or dams have on Salmon migration?

Many in-stream barriers, such as dams and weirs, can make fish migration more difficult, but they can also help with flood control and invasive species management.

In the Humber River, for example, the structure at Etienne Brule park keeps invasive Sea Lamprey and Round Goby from moving upstream. The “notch” in the centre of the structure is lower and this modification improves access for Salmon.

Other weirs in the City, such as the one in Raymore Park along the Humber River, have fish ladders built in to help fish navigate their way upstream.

Salmon are powerful jumpers, capable of reaching three or more metres, so most make it upstream! If you go upstream you will see abundant Salmon splashing around in the shallows.

The consideration to remove or modify a dam can be a delicate balance between public safety and ecology. Decisions around modifications to or removal of in-stream man-made barriers are made in consultation with our municipal, provincial, and federal partners, with input from the public and other stakeholders.

Why am I seeing dead Salmon in the rivers and streams in late September, October, and November?

It is a natural part of their life cycle for many Pacific Salmonid species, such as Coho and Chinook, to die after they spawn (i.e. lay eggs). Dead salmon are an important food source in the river ecosystem and their decomposition adds important nutrients to the waters.

Unlike Pacific Salmon, Atlantic Salmon do not die after spawning, so they can repeat the spawning cycle multiple times.